LA SALITRERA, San Luis Potosí – Backhoes rapidly break down what decades ago was a pine and oak forest. Traca-tatatata-traca-tatatata. The mechanical rattling disrupts the silence of Sierra de Álvarez, one of 40 Flora and Fauna Protection Areas (APFF) in Mexico, just a few miles away from the world’s largest fluorspar mine.

Daniel guards a steep slope next to the tailings dam No. 4, authorized since 2016 by the Mexico’s Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT) to store waste from fluorite extraction in a 21-hectare area. His boots slip on soft sandstone marked by tractor tracks.

“Whose land is this?” he is asked.

“These are community lands, but Koura works them,” says Daniel, dressed in his work overalls.

While a drizzle makes the dam slosh, Daniel adjusts the pipe as if pulling the veins of a beast excreting earthy waste. In front of him stand trees submerged to the top: black as rotten bananas, completely poisoned. A lifeless nature.

Downhill, a muddy road winds its way to one of the curtains of the 22-hectare tailings dam No. 6, in operation since 1982. From the top of El Órgano hill, an attraction for hikers in Sierra de Álvarez, one can see how the mine eats away Sierra like leprosy eats away the human body.

La Salitrera is a community trapped in an industrial wasteland – claws of machines that once gutted the mountains, rusty tanks, industrial warehouses, miles of hoses that spread along the roadside. It only has a small rural medical unit operated by the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS), where care is scarce due to a shortage of doctors.

Although La Salitrera is in the municipality of Villa de Zaragoza, Koura has made that community its own. Personnel transport, dump trucks, gigantic machinery escorted by trucks with sirens and flags, travel on a semi-paved road from Villa de Zaragoza to La Salitrera guarded by private security guards and a video surveillance system with cameras with 360º rotation.

Villa de Zaragoza is a mining site where not only fluorite is extracted but also lime (Cal Química Mexicana S.A. de C.V., in the Los Matías community), calcium carbonate and phosphoric rock (Triturados Gramol S.A. de C.V). But the municipality does not have Wastewater Treatment Plants (WWTP) in the communities with the largest number of inhabitants, such as the municipal seat, Cerro Gordo, la Esperanza and San José de Gómez.

The lack of basic services in Villa de Zaragoza, just 30 minutes from the city of San Luis Potosí, is evident – unpaved roads, malodorous rivers, tangled wires, vans full of water jugs gnawed and dented due to usage. In addition, it is the second most violent municipality of San Luis Potosí after Vanegas, with a rate of 70.8 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, according to records of the Executive Secretariat of the National Public Security System (SESNSP).

The highest point of La Salitrera is a roof with the legend Koura in blue letters on a green background. At one of the entrances, the cattle graze in front of a mountain of crushed stones. On the way, the donkeys cross with a parsimony that irritates the truck drivers who transport the newly extracted material.

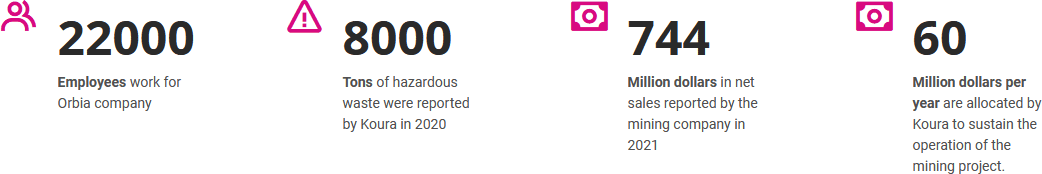

Koura is the fluorinated solutions business group of Orbia Advance Corporation, S.A.B. de C.V. and accounted for 8 percent of the conglomerate’s sales in 2021. Last year the mining company reported net sales of $744 million, that is, more than double the 2022 federation’s expenditure budget, which was around $370 million. To maintain the operation of the mining project, Koura allocates $60 million annually, the same price at which a pink diamond extracted from the Mwadui mine in Tanzania was sold and auctioned in Hong Kong by Sotheby’s in mid-October.

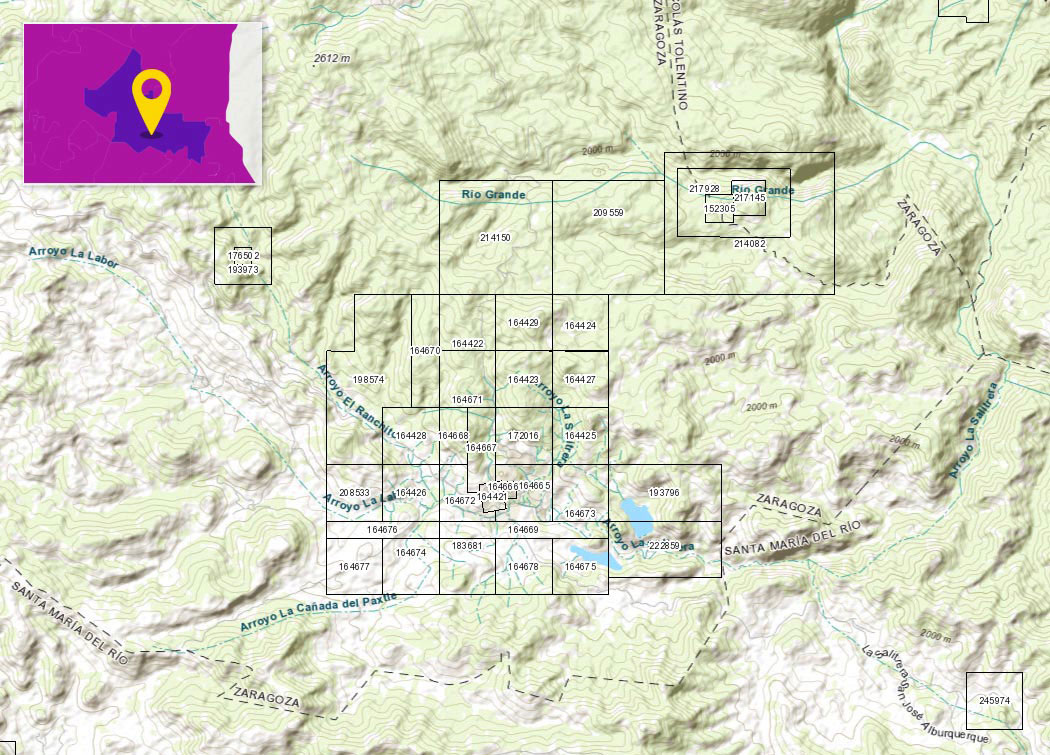

The Las Cuevas mining unit has had concessions since 1978, although the fluorite deposit has been exploited since 1955, when it was expected to have a future of six decades. In 2025 it will be 70 years since this non-metallic mineral is extracted. The company owns at least 33 mining lots – all properly registered – that cross the streams La Cañada del Paxtle, La Labor, La Salitrera and El Ranchito.

The plots of land from which fluorite is extracted are named after states of the Mexican Republic. A mile away from the Sierra de Álvarez Flora and Fauna Protection Area is the Yucatán lot, where the Grande River crosses mining concession 214150, granted in 1997 during the administration of former President Ernesto Zedillo. Next to this lot is Hidalgo, with the same dimensions (400 hectares) followed by these other lots: Michoacán, Jalisco, Sinaloa, Sonora, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Tabasco, Durango, Nuevo León, Campeche, Zacatecas, Veracruz, Tamaulipas, Guerrero, Oaxaca, La Consentida and La Virgen, just to mention a few.

Mexico is the country with the most fluorite reserves (20% worldwide), followed by China (19%) and South Africa (13%). The uses of the fluorite extracted in La Salitrera are intended for the production of hydrofluoric acid, aluminum fluorideand refrigerant gases, which accelerate the destruction of the ozone layer. With this non-metallic mineral, Koura serves a fluoride supply chain that includes Mexico, the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Japan and Taiwan.

Orbia Advance Corporation, S.A.B. de C.V. – until 2019 called Mexichem – is owned by Antonio del Valle Ruiz and his family, the seventh most wealthy in the country, with an estimated fortune of $3.1 billion, according to the Forbes 2021 ranking. Del Valle Ruíz led the bankers when their liabilities became public debt through Fobaproa in 1998. Currently, through the Kaluz Foundation, directed by Blanca del Valle Perochena, it maintains, with millionaire donations, the operations of the Mexican Business Council (CMN), the “top leadership” of the private sector that brings together the richest and most powerful entrepreneurs in the country.

Del Valle Ruiz, 89, is so wealthy that he could afford to found the Kaluz Museum where he accumulates a collection of works by some of Mexico’s most revered artists, including David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, Juan Soriano, Dr. Atl, and Juan O’Gorman. Last January, Del Valle Ruiz told the newspaper El País, “Instead of buying companies, I am now buying paintings.”

His power is so great that it was in the Kaluz Museum where President Andrés Manuel López Obrador met last June and December with members of the Mexican Business Council, in charge of his son Antonio del Valle Perochena, who also chairs Grupo Kaluz, which administers Orbia, Elementia, Grupo Financiero Ve Por Más, Byline Bank and Innova Schools Mexico.

The del Valle Perochena family appeared among the beneficiaries of offshore structures, released in October 2021 as part of the global #PandoraPapers investigation. In 2015 Francisco Javier del Valle Perochena, son of the patriarch and chairman of the board of directors of Elementia, joined the paper company Seafort Management, created in the British Virgin Islands (BVI), which owned a $977,000 yacht. The company was created by the producer and director of the loan company Leasing, Javier Muñiz Canales, and the shipping entrepreneur Alfredo Kunhardt.

In its 2021 annual report, Orbia Advance Corporation, S.A.B. de C.V. – whose president of the administration board is Juan Pablo del Valle Perochena – practically disregards its activities and the impact they may cause both on nature and communities.

“Orbia produces, distributes and transports hazardous materials as part of its operations, implying risks of leaks and spills that could potentially affect both people and the environment. The company also produces, distributes and sells products that are dangerous or have certain levels of global warming potential that may become restricted in the future,” reads page 35 of its 2021 annual report, a comprehensive document that is a requirement for listing on the stock markets.

Orbia has commercial activities in more than 100 countries and more than 22,000 employees. Koura is one of the five brands in the cluster, including Vestolit and Alphagary (polymer solutions), Wavin (building and infrastructure), Netafim (precision agriculture) and Dura-Line (data wiring).

While placing its debt in sustainability-linked bonds, Orbia warns its investors about the intricacies of the mining business. “The company cannot assure that it has been and at all times will be in full compliance with such laws, regulations and permits (...) Orbia may also be liable for any consequences arising from human exposure to hazardous substances or any other environmental damage.”

Orbia downplays concerns about national and international environmental laws and regulations. “Environmental protection laws are complex, change frequently and tend to become stricter over time.”

Of a total system of seven dams, intermediate tailings dams No. 1, 2, 3 and 4 have already concluded their useful life, according to an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for the project “Operation of the Las Cuevas mining unit,” published in 2019 by Mexichem Flúor S.A. de C.V., which invested $13.5 million to close and abandon them. However, they plan to conclude operations within 60 years, that is, until 2079. In the meantime, in the dams, trees are agonizing in the mud.

“In the case of environmental risks caused by the project, the most significant one is the risk of dam collapse, and failure to implement corrective measures could result in fatal consequences and irreversible impacts for the environment and the community,” explained the EIA, prepared by Environmental Resources Management (ERM), a consulting firm that prepares environmental assessments for ExxonMobil, Shell, Valero, Ford, Syngenta, and for organizations such as the United Nations and the World Bank.

The Koura mine, until 2019 known as Mexichem Fluor, not only affects the margins of the Sierra de Álvarez, it also affects the area surrounding the “El Potosí” National Park. According to the environmental impact study, the mine accumulates damage on the margins of Sierra de Álvarez: “There are seven significant direct impacts generated by the project,” the study said. However, “with the respective application of environmental management measures, the potential impacts can be efficiently reduced and minimized.”

Impacts include soil, subsoil, and water pollution from oil and diesel leaks or spills. Risks to workers include falls, inhalation, absorption, or ingestion of hazardous substances; being trapped on, between, or inside objects; overexertion; and use of tools and equipment in unsafe conditions, among others.

In 2020, the Koura mine reported the production of approximately 8,000 tons of hazardous waste (43% less than in 2019). It also produced approximately 163,747 tons of hardened earth, which, to a lesser extent, is used to reinforce the outer banks of the containment barriers of the tailings dams. However, that hardened earth can increase erosion and prevent aquifer recharge, according to a study by the Geology Institute of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).

In addition, the mining project has three pumping stations that supply water to the mining crushers: Arroyo, Los Chivos and La Laguna. Due to the lack of public services, Koura also installs a drinking water network in the homes that request it. To do so, it runs its pipelines through the mountains.

According to Official Mexican Standard, NOM-141-SEMARNAT – to which the mining activity adheres – “the tailings dams are one of the systems for the final disposal of solid waste generated by the benefit of minerals and must meet conditions of maximum safety, in order to guarantee the protection of the population, economic and social activities and, in general, the ecological balance.”

Mining is an activity that affects water, air, soil and biodiversity. Its impacts on the environment include loss of vegetation cover, soil and habitat, alterations to air quality, generation of acid mine drainage, alterations to groundwater, generation of seismic vibrations, contamination with substances or materials used in extraction, and displacement of species.

Article 36 of the regulations of the General Law on Ecological Balance and Protection of the Environment regarding Hazardous Waste stipulates, “The tailings dams may be located in the place where said waste originates or generates, except above populations or receiving bodies located at a distance of less than 25 kilometers that could be affected.”

Although SEMARNAT is responsible for supervising all mining corporations operating in the country, budget constraints prevent inspectors from traveling regularly to sites reported by the companies in their environmental impact reports.

SEMARNAT visited La Salitrera on at least four occasions, the first due to a mine waste spill as a result of the rupture of a pipeline under maintenance, in September 2000. Subsequently, the Environmental Ministry carried out three other inspections in the field of hazardous waste on October 2013, September 2015 and October 2020, where only “administrative irregularities” were reported, which resulted in a fine of almost 40,000 Mexican pesos.

María Luisa Albores González, head of SEMARNAT, warned last December of the damage caused by the tailings dams, which represent a risk for the communities settled in the surrounding areas, during the presentation of the “Preliminary Approved Inventory of Tailings Dams”, which records 585 landfills throughout the country, more than half of them still in operation. Durango, Chihuahua, Zacatecas and Sonora are the states with the highest number of such toxic landfills.

This inventory only counts three – two of them inactive – of the seven dams currently operating at the Las Cuevas mining unit. “It may be that there is an inconsistency with what is in the field and what is on the map, the inventory is under construction, it is a pending issue,” explains Alonso Jiménez Reyes, Assistant Secretary of Environmental Regulation at SEMARNAT.

“Mapping is required in order to close the inventory gap, to limit any area of illegality, ignorance or lack of supervision,” says Jiménez.

–What is the impact of the tailings dams?

“The main risk in general is that a spill may occur in the tailings dams that are close to the rivers,” Jiménez explains. “A well-built dam should not leak. It can spill if its level goes beyond its capacity. It can also release dusts even when in disuse that could have a negative impact, so we must ensure that the closure process is adequate and that it is properly monitored to avoid such damage.”

–Are mining companies committed to the environment?

“They must be, it is not optional. Over the years they have been seeking to operate in an orderly manner with the environment, but the operation of the mine is an activity that has a direct impact on the environment.”

–Have you received bribes from Orbia to get a favorable opinion?

“Neither from Orbia nor from anyone else, such things are not allowed,” Jiménez says.

–How can economic development be achieved without harming the environment and communities?

“Development must be built from the territory, seeking a dialogue with citizens, asking how they want to share the wealth generated in their communities. It must grow in a sustainable way, ensuring that it is possible to continue living.”

A tour of the Koura fluoride mine was requested, but the request was denied. A questionnaire was also sent, but the company responded with a disclaimer, “Any impact that the company may cause is expected and can be addressed with prevention or mitigation measures that reduce the impacts and do not affect the ecological balance. An example of this is the investment and permanent monitoring of our dams, to maintain their safety, and even improve their structures.”

On the outskirts of the industrial warehouse, on the edge of the tailings dam La Consentida, as 69-year-old Homero Hernández drives through a curtain of fog, he remembers his days as a miner.

“I started down there in the mine, breaking stone with a sledgehammer. There were no machines back then. Each one of us would take a section of two rails to break the stones and throw them into small wagons. Then I was an assistant installing props, putting the timbers in the tunnels that were being opened,” he says as he walks past an industrial contraption.

–How many floors does the mine have?

“I worked on level 150, 180, then 220. By now there must be more than 400 levels.”

–And what’s it like inside?

“An underground city where many accidents have happened.”

After working for several years in the depths of La Salitrera, Homero decided to migrate to Florida, where he worked in the orange harvest and later to Michigan with apple harvest. He spent a couple of years in the United States until his mother Amparo was close to death.

“My mother told me to come, to bury her and afterwards I could go back. But I stayed,” says Homero.

–Why didn’t you go back to the mine?

“I got old and they didn’t need me anymore.”

–Did you receive severance pay?

“With the scarce money one gets.”

–Is there any opposition to the mine?

“Not right now, because the mine has the obligation to provide jobs for the whole community. People come from Villa de Zaragoza, Durango, Zacatecas, Sonora.”

Homero and his wife Antonieta found in cooking a way to survive, opening a small restaurant. At the Doña Toña restaurant, three contractors from Electrical and Industrial Services (SEEISA) recharge their energy with an exquisite pork entomatado with rice and beans. In front of a pink, weathered wall sheltered by a small painting of the Virgin of Guadalupe, they eat in a hurry because they have to return to work.

“My wife’s cooking has a flavor that stands out,” says Homero emphatically, convinced that the mine brings life to the people of the community.

Among the blurred silhouettes of oak trees, outside Don Chuy’s store – the only store in La Salitrera – a man writhes on a bench, next to a carton of beers and three loyal dogs that watch over him while he drinks.

In addition to taking over the community and altering the landscape, the most visible thing that Koura has done is to put up signs with phrases printed on aluminum: “Are you carrying your wallet? Are you carrying your cell phone? Are you carrying your garbage?”

We don’t have a paywall because, as a nonprofit publication, our mission is to inform, educate and inspire action to protect our living world. Which is why we rely on readers like you for support. If you believe in the work we do, please consider making a tax-deductible year-end donation to our Green Journalism Fund.

Donate